Editorial Note:

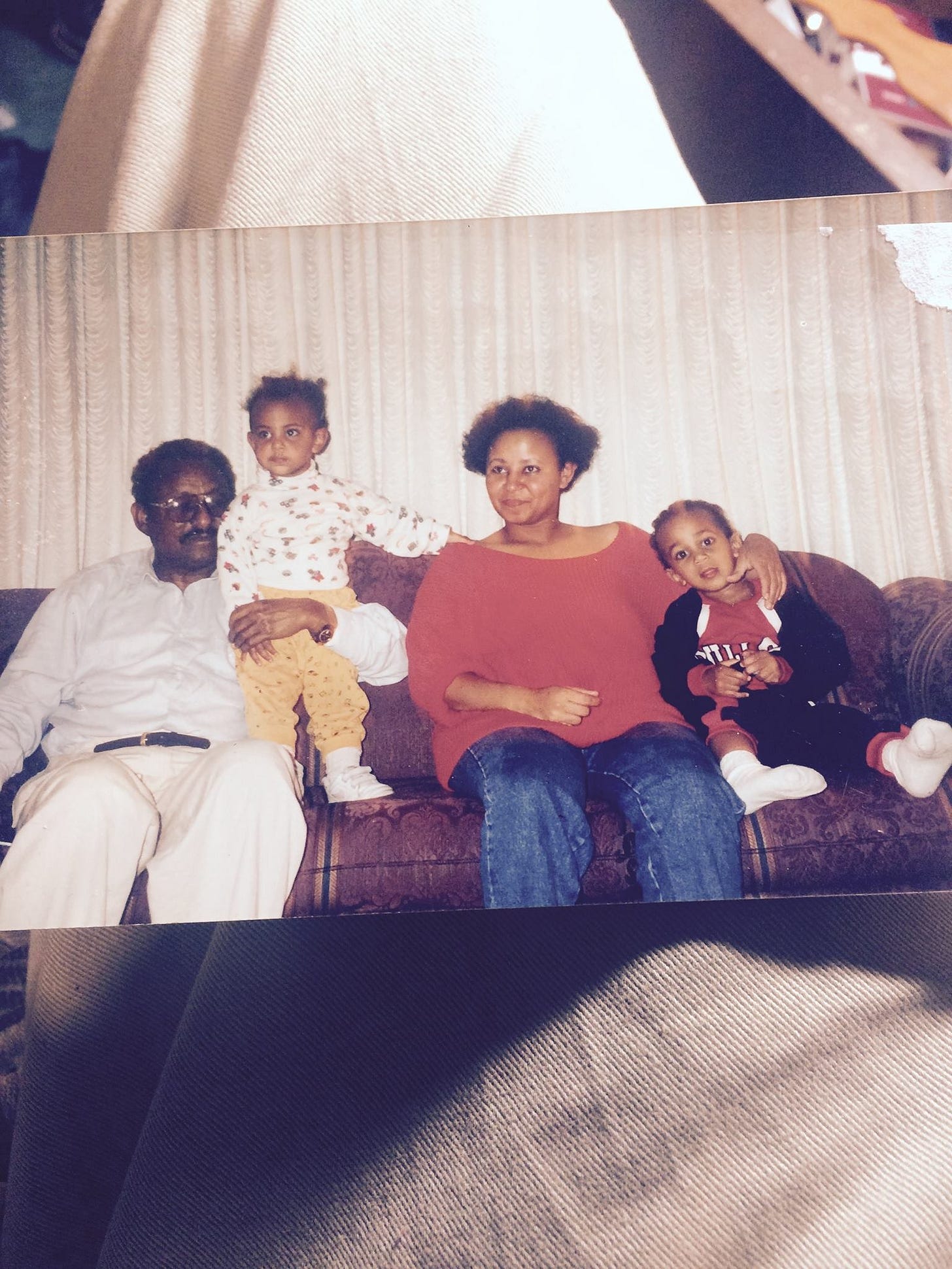

Any reader who is in a rush can purchase this text hither, or swiftly punch in the text’s title in their search engine of choice to find it for free. There are several new readers here from Mars Review of Books, Journal of Free Black Thought, The Voice of the Shepherd, and 𐍃𐌺𐌴𐌹𐍂𐌴𐌹𐌽𐍃. Welcome. What I do here is Ge’ez (Classical Ethiopic) and Amharic (Neo-Ethiopic) interpretation and translations, biblical commentaries, and republishing and editing historical works in Ethiopian Studies and Americana. The following is the original preface to A Narrative of Captivity in Abyssinia, by its author Dr. Henry Blanc (an English medical doctor and diplomat/spy), and my maternal grandfather’s (an Ethiopian teacher, school administrator, and diplomat) introduction to his English to Amharic translation of this work in the late 1980s and early 1990s. My grandpa fell asleep with the Lord in 1995. I knew him in the flesh for five short years, but have known him in the spirit through his writings throughout my 20s and 30s.

With Some Account of the Late Emperor Theodore, His Country, and People

Henry Blanc M.D,

M.R.C.S.E., F.A.S.L.,

Staff Assistant-Surgeon Her Majesty’s Bombay Army

(Lately on Special Duty in Abyssinia)

London: Smith, Elder and Co. 1868.

Preface

With a view of gratifying the natural curiosity evinced by a large circle of friends and acquaintances to obtain accurate information as to the cause of our captivity, the manner in which we were treated, the details of our daily life, and the character and habits of Theodore, I undertook the task of writing this account of our captivity in Abyssinia.

I have endeavored to give a correct sketch of the career of Theodore, and a description of his country and people, more especially of his friends and enemies.

In order to make the reader familiar with the subject, it was also necessary to say a few words about the Europeans who played a part in that strange imbroglio—the Abyssinian difficulty. My knowledge of them, and of the events that occurred during our captivity, was acquired through personal experience, and also by intercourse with well-informed natives, during long months of enforced idleness.

In preparing this work for the press, I found it necessary to the completeness of the narrative, to incorporate some portions of my report to the Government of Bombay on Mr. Rassam’s mission, which appeared in an Indian newspaper, and was subsequently republished in a small volume.

For the same reason I have also included a few articles contributed by me to a London newspaper.

The sufferings of the Abyssinian captives will be ever associated, in the annals of British valor, with the triumphant success of the expedition, so skillfully organized by its commander, whose title, Lord Napier of Magdala, commemorates the crowning achievement of a glorious career.

London, July 23, 1868.

Notes:

-Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons of England

-Fellow of the Antiquarian Society of London

-The Magdala (Meqdela in Ge’ez) referenced is a hilltop fortification in the highland plateaus of Ethiopia, not the one for which it is named in the bible and in the modern-day land of Israel. Historically, it is in the dominion of Welo, a part and parcel of the modern-day Amhara Region, from whence I overwhelmingly hail.

Introduction

By: Dañew Welde’Silasé (of Wiki Leaks fame)

People without a history are not eager to do historical work. People who do not know freedom do not tire to achieve freedom. Since Ethiopia is an awe-inspiring free country with a history that spans eras, it is a necessity that her children, knowing her history, protect her spire of freedom. If one (Ethiopian) young person tries to wax poetically about the history of Europe and America, without knowing and finishing their own history, they will be as embarrassing as the saying goes, “when asking the mule, who is your father? He responds, the horse is my uncle.”

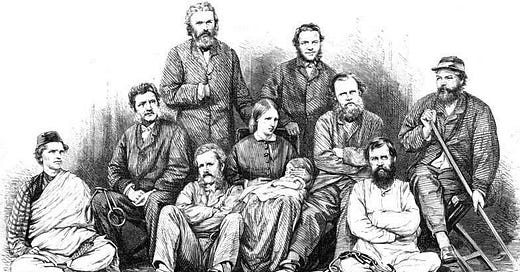

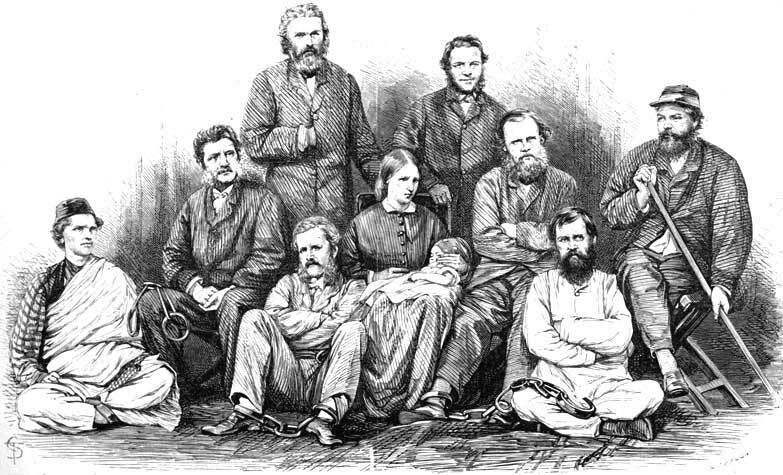

A hundred years ago, the Englishman called Dr. Henry Blanc and Mr. Rassam were imprisoned by Emperor Theodore at Magdala. In order to have English Consul Cameron and his followers released, Blanc and Rassam brought a letter from the Queen of England to Emperor Theodore. Emperor Theodore received them with honor, and released the prisoners. But then, after a circumstance, he imprisoned them all again, and sent them to Magdala, where for two years they were in chains. Since Blanc was one of these prisoners, he wrote an account of his eyewitness testimony: about the era of their imprisonment, about Emperor Theodore, and about habesha people in A Narrative of Captivity in Abyssinia. My beloved friend Mr. Birhanu Deenqa gave me this book. After reading it, I felt an elevated sense of awe at the things uncovered inside. Even if this book was printed a hundred years ago, and written in English, since I understood it was as hard to find as a heart, I believed it would satisfy the wants of many history lovers, and so I translated it into Amharic.

He who reads this book meticulously will without a doubt understand that there is nothing Emperor Theodore did not try to do, during the era of his kingdom, to enter Ethiopia into the path of modernity.

For example, rather than his country’s or his own honor being touched he chooses death. The hero of heroes Theodore, in order to find European craftsmen to teach his people blacksmithing, in his letter to Mr. Rassam he references the story of Solomon and Hiram. “Besides asking Mr. Flad and the sent metal workers to come via Metema, and fostering love with the great queen, her princes, and her people, I have no other way.” His body that does not like humiliation can be seen changing his ways, becoming a blacksmith for the function of serving his people who eagerly look toward him. The mighty Theodore became the first mover and founder of Ethiopia’s first cannons made on Ethiopian soil, for the sake of Ethiopian growth and development. Furthermore, he personally philosophized (created) a ship’s motor, becoming a father of the philosophy of craftsmanship. The mind is filled with expansive awe when it considers with the lyre of engrossment and concentration that this was done and philosophized a hundred years ago. It awakens the vigor of work. He is the perfect example and an awesome and wonderful image for Each one of us, to labor on behalf of our beloved mother country and fulfill the portion she is owed. Let us not be reserved in blessing her.

It is true, without a doubt, that in the future still much about Theodore the Great’s war tempo, tactics, bravery, heroism, laying the foundation of his country’s oneness and unity, his upright purpose for the growth of his country, his love of craftsmanship, his craftsmanship philosophizing, the depths and distance of his research of literature, and the awesomeness of his judgments will be written about with inquiry and exposition.

In the first print edition some readers asked, “was the harshness of Emperor Theodore necessary?”

In the era in which Emperor Theodore reigned Ethiopia was divided amongst hereditary princely rulers and their followers, becoming their livelihood. This was an era in which her ancient history was distorted. As it is necessary to destroy all crooked houses in order to straighten them again, Emperor Theodore was forced to use might in order to take Ethiopia out of the hands of these princely rulers, fostering her oneness and protecting her freedom. Were he not to use might, he would have been no different than any of the other princely rulers of the time.

If a parent forces their child to take medicine, or as it is done in our country, spanks the child as they force them to drink the medicine, can they be called harsh? It is certainly harsh when they spank the child. However, as we look at the reason for the harshness, they were thinking of the wellness of the child, to save them and protect them from the heavy harm brought about by the sickness, and thus the action cannot be called harsh. On the other hand, if a father, without a reason, has a habit of beating his child day and night, he would correctly be called harsh.

History tells us that when Emperor Theodore arose, his first purpose was to make Ethiopia one, as in ancient times, to protect her freedom from those enemies coming in from every which direction trying to steal it. The problems he faced again gathering an Ethiopia that had stayed divided for more than 70 years, and strengthening the institution of her foundation, were not easy. It is not that these hereditary princely rulers did not wish to make Ethiopia one and rule her. Rather, only having the wish to destroy others to totally rule the country is not enough. It is necessary to spend a lot of time on many war fronts, to know the tactics and tempo of war, and to be found with an enduring spirit. There was no man the Lord chose for this deed but Theodore. It was necessary for Emperor Theodore, with the might of his troops, to destroy the hereditary princely rulers where they were. After a hundred years, it is good for us to understand that the punishments he carried out were necessary in that time, and not in our own time. The choice was to leave Ethiopia divided as she was, or to have a king of kings like Theodore, agreeable to that time. The Lord is good. We have been able to receive Ethiopia’s oneness and freedom, with a few of our fathers as sacrifices with the Lord’s arising of Theodore.

Since in Theodore’s era preaching and softness were not as fruitful as might, Theodore used might in the correct way. As it was difficult for our fathers of the time to receive the punishment, their sacrifice is not to be forgotten.

As it is seen in this book, whose English author was tortured and imprisoned in chains until the handles of his feet were peeled, Theodore hammered those hereditary princes arising in all dominions to destroy Theodore’s purpose and protect their hereditary principalities. However, with his great army estimated to be 150,000 scattered, holding less than ten thousand soldiers, the English troops who were superior in their weaponry and their abundance of soldiers and in their war tempo, when they reached and met at the mouth of Magdala, when he realized he was defeated by scouts alone, to protect the honor of Ethiopia’s crown, he decided to kill himself. A few hours later, he released the English prisoners that were the reason for this suffering, so that they could peacefully go to the English troops’ encampment. As he was captured, the advisors around him were pulling him to kill the prisoners, and he said, “were not the people exterminated in the past two days enough? Do you all want me to kill these whites, and bathe habeshas in blood?” This reply he gave to one advisor is enough testimony to know that all of the things he did were not sprung forth from harshness, but to complete judgment and fulfill his purpose. The reader of a hundred years later can look at the modernity of Ethiopia and her people to weigh that overall his deeds were not harsh.

To understand his awe-inspiring story, to deep dive, let us read this book. If there is anyone who says since Dr. Henry Blanc was tortured by Emperor Theodore, and a foreign citizen, he wrote this from an eye of enmity and bias, they should know he is an eye witness who followed up with this account over time and prepared it. Any researcher who focuses and looks at this story, and the spirit that carries this book on its back, can weigh and understand the truth from deceit, the wheat from the chaff, and the gold from the grit.

Notes:

-The Ge’ez hzb (people), is a loan-word to the Arabic (perhaps as far back as during the First Hijrah aka the Migration to Abyssinia), popularized by Hezbollah (the people/party of God), whom you may have heard in the news of late

-Mr. Rassam is an ethnically Assyrian Assyriologist of Ottoman Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq, employed by the British Empire

-(h)atsé (Ge’ez for emperor), literally means he who holds the kingdom in his embrace. From this same consonantal root, we have: hitsan (infant/suckling), mahitsen (womb). iCHegé (abbot of the Debre Leebanos monastery of the historic Shewa Dominion who is in close proximity to the emperor, collects taxes, and his the honorary head of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahdo Church, second only to the metropolitans sent from the holy synod in Alexandria Egypt, See of St. Mark the Evangelist), and iCHoña (betrothed; fiancé).

-igre muq (the foot of warm), says my grandpa’s orginal Amharic manuscript. Likely an Amharic butchering of the Ge’ez moqha igr (prisoner of the foot).

-silTane is literally authority, but dynamically modernization and higher levels of civilization

-keene tibebat tebeeb is quite a phrase to translate. keen is skill, and Tibeb is wisdom. I dynamically translated this as craftsman and craftsmanship, but it is literally a wise man with the skill of wisdoms. In Arabic and in Amharic this could also be a wise man, like hakeem, or a medicine man / medical doctor.

-1 Kings 5 is the reference of Solomon and Hiram

-Amharic afer (soil) is the same consonantal root as the Biblical Hebrew dust or dirt of Genesis, from whence we were all made in his image and likeness, after having been breathed upon by his nostrils (which can also turn to wrath).

-senezere - the Amharic verb to ask is literally to stretch out one’s arm, it can also be to aim

-gezh - the Amharic word for ruler is literally owner; following the semitic melek/mlk, which in Ge’ez and Amharic is amlak, usually reserved for God alone, but there are rare exceptions like in the hymns of the EOTC where as a verb rather than a noun, “he made the sun to rule over the moon”.

-the author/translator Dañew is himself a descendant of these hereditary princely rulers he critiques. His great great uncle Wibé Haylemaryam (who ruled neighboring Tigray and the Eritrean highlands, where songs of his harshness are still sung, from his throne in Welqayt, modern-day Amhara Region) was the last of these to be defeated by emperor theodore, being put in golden chains, and Wibé’s daughter Tiru’Werq, Dañew’s great aunt, who was on the path to being a nun was forced to be Theodore’s wife, and from this forced union Dañew’s uncle, or in American parlance his second-cousin once-removed, the tragic Crown Prince Alem’Ayehu was born. Still, Dañew favors Emperor Theodore, over his own flesh-and-blood, because he saw Ethiopia as a whole as greater than his family and tribe alone. The blood of the covenant is thicker than the water of the womb.

-irgiT - the Amharic word for certainty or verification has the connotation of stepping upon something to certify or verify.

-Dañew makes reference to The Scramble for Africa and The Era of Princes, both of which would benefit from a Game of Thrones style (without the gratuitous nudity, like the modest Rings of Power, whatever else you may say of that series Tolkien friends)

-Teqlay gizat - the Amharic word for dominion, realm, province, prefecture region etc. was on the mouthes of my parents and extended family members who arrived in the U.S. in the 1970s. The next generation, who knew the Marxist-Leninst military junta known as the Derg said kfle hager (partition of the country), and the TPLF generation said kilil (protectorate).