Henry Blanc, M.D.

Chapter I.

The Emperor Theodore–His Rise and Conquests–His Army and Administration–Causes of his Fall–His Personal Appearance and Character–His Household and Private Life.

Prince Kasa (recompense), better known as the Emperor Theodore, was born in Qwara about the year 1818. His father was a noble of Abyssinia, and his uncle, the celebrated Gate-Commander Kinfu, had for many years governed the provinces of Dembeeya, Qwara, CHilga, &c. On the death of his uncle he was appointed by Duke Ali’s mother, Mrs. Menen, governor of Qwara; but, dissatisfied with that post, which left but little scope for his ambition, he threw off his allegiance, and occupied Dembeeya as a rebel. Several generals were sent to chastise the young soldier; but he either eluded their pursuit or defeated their forces. However, on the solemn promise that he would be well received, he repaired to the camp of Duke Ali. This kind-hearted but weak ruler thought to attach to his cause the brave chieftain, and to accomplish that object gave him his daughter Tewabech (she became beautiful). Prince Kasa returned to Qwara, and for a time remained faithful to his sovereign. He made several plundering expeditions in the lowlands, carried fire-and-sword into the Arab huts, and always returned from these excursions bringing with him hordes of cattle, prisoners, and slaves.

The successes of Kasa, the courage he manifested on all occasions, the abstemious life he led, and the favor he showed to all who served his cause, soon collected around him a band of hardy and reckless followers. Being ambitious, he now formed the project of carving out an empire for himself in the fertile plains he had so often devastated. Educated in a monastery, he had not only studied theological subjects, but made himself conversant with the mystic Abyssinian history. His early education always exercised great influence on his after-life, giving to his intercourse with others a religious character, and impressed vividly upon his mind the idea that the Mussulman race having for centuries encroached on the Christian land, it should be the aim of his life to re-establish the old Ethiopian Empire. Urged on, therefore, both by ambition and fanaticism, he advanced in the direction of Gedaref (Ottoman Sudan) at the head of 16, 000 warriors; but he had soon to learn the immense superiority of a small number of well-armed and well-trained troops over large but undisciplined bodies of men. Near Gedaref he came in sight of his mortal foes the Turks, a mere handful of irregulars; yet they were too much for him: for the first time, defeated and disheartened, he had, for a while, to abandon his long-cherished scheme.

Instead of returning to the seat of his government, he was obliged, on account of a severe wound received during the fight, to halt on the frontier of Dembeeya. From his camp he informed his mother-in-law of his condition, and requested that she would send him a cow—the fee required by the Abyssinian doctor. Mrs. Menen, who had always hated Kasa, now took advantage of his fallen condition to humble his pride still more; she sent him, instead of a cow, a small piece of meat with an insulting message. Near the couch of the wounded chieftain sat the brave companion who had shared his fortunes, the wife whom he loved. On hearing the sneering message of the Queen, her fiery Gala blood flamed with indignation. She rose and told Kasa that she loved the brave but abhorred the coward; and she could not remain any longer by his side if, after such an insult, he did not revenge it in blood. Her passionate words fell upon willing ears; vengeance filled the heart of Kasa, and as soon as he had sufficiently recovered he returned to Qwara and openly proclaimed his independence.

For the second time Duke Ali called him to his court; but the summons met with a stern refusal. Several generals were sent to enforce the command, but the young soldier easily routed these courtiers; whilst their followers, charmed with Kasa’s insinuating manners and dazzled by his splendid promises, almost to a man enrolled themselves under his standard. His wife again exerted her influence, showing him how easily he might secure for himself the supreme power, and, as he hesitated, again threatened to leave him. Kasa resisted no longer; he advanced into Gwejam, and carried all before him. The battle of Djisella, fought in 1853, decided the fate of Duke Ali. His army had been but for a short time engaged when, panic-stricken, the duke left the field with a body of 500 horses, leaving the rest of his large host to swell the ranks of the conqueror. Victory followed victory, and after a few years, from Shewa to Metema, from Gwejam to Bogos, all feared and obeyed the commands of the Emperor Theodore; for under that name he desired to be crowned, after he had by the battle of Deraskié, fought in February, 1855, subdued Tigré, and conquered his most formidable opponent, Gate-Commander Wibé.

Shortly after the battle of Deraskié, Theodore turned his victorious arms against the Welo Galas (heathens; usually pastoralist Oromo), possessed himself of Magdala, and ravaged and destroyed so completely the rich Gala plain that many of the chiefs joined his ranks, and fought against their own countrymen. He had now not only avenged the long-oppressed Christians, so often victims of the Gala inroads, but curbed for a long time the haughty spirit of these clans. At the height of success, he lost his brave and loving wife. He felt the cruel blow deeply. She had been his faithful counselor, the companion of his adventures, the being he most loved; and he cherished her memory while he lived. In 1866, when one of his artisans almost forced himself into his presence to request permission for me to remain a few days near the man’s dying wife, Theodore bent his head, and wept at the remembrance of his own wife whom he had so deeply loved.

The career of Theodore may be divided into three very distinct periods:—First, from his early days to the death of his first wife; secondly, from the fall of Duke Ali to the death of Mr. Bell; thirdly, from this last event to his own death. The first period we have described: it was the period of promise. During the second—which extends from 1853 to 1860—there is still much to praise in the conduct of the Emperor, although many of his actions are unworthy of his early career. From 1860 to 1868 he seems little by little to have thrown off all restraint, until he became remarkable for reckless and wanton cruelty. His principal wars during the second period were with Gate-Commander Goshu Biru, governor of Gwejam; with Gate-Commander Wibé, whom he conquered, as we have already stated, at the battle of Deraskié, and with the Welo Galas. He could, however, still be merciful, and though he imprisoned many of the feudal chiefs, he promised to release them as soon as the pacification of his empire should be complete.

In 1860 he advanced against his cousin Gered, the murderer of Consul Plowden, and gained the day; but he lost his best friend and adviser, Mr. Bell, who saved the Emperor’s life by sacrificing his own. In January, 1861, Theodore marched with an overwhelming force against a powerful rebel, Agew Nigusé, who had made himself master of all northern Abyssinia; by cunning and skilful tactics, he easily overthrew his adversary but tarnished his victory by horrid cruelties and gross breach of faith. Agew Nigusé’s hands and feet were cut off, and though he lingered for days, the merciless emperor refused him even a drop of water to moisten his fevered lips. His cruel vengeance did not stop there. Many of the compromised chiefs, who had surrendered on his solemn pledge of amnesty, were either handed over to the executioner or sent to linger for life, loaded with fetters, in some of the prison ambas (hilltops). For the next three years Theodore’s rule was acknowledged throughout the land. A few petty rebels had risen here and there, but with the exception of Tedla Gwalu, who could not be driven from the fastness of his amba in the south of Gwejam, all the others were but of little importance, and did not disturb the tranquility of his reign.

But though a conqueror, and endowed with military genius, Theodore was a bad administrator. To attach his soldiery to his cause, he lavished upon them immense sums of money; he was therefore forced to exact exorbitant tributes, almost to drain the land of its last dollar, in order to satisfy his rapacious followers. Finding himself at the head of a powerful host, and feeling either reluctant or afraid to dismiss them to their homes, he longed for foreign conquests; the dream of his younger days became a fixed idea, and he believed himself called upon by God to re-establish in its former greatness the old Ethiopian empire.

He could not, however, forget that he was unable to cope single-handed with the well-armed and disciplined troops of his foes; he remembered too well his signal failure at Gedaref, and therefore sought to gain his long-desired object by diplomacy. He had heard from Bell, Plowden, and others, that England and France were proud of the protection they afford to Christians in all parts of the world; he therefore wrote to the sovereigns of those two countries, inviting them to join him in his crusade against the Mussulman race. A few passages selected from his letter to our Queen will prove the correctness of this assertion. “By his power (of God) I drove away the Galas. But for the Turks, I have told them to leave the land of my ancestors. They refuse!” He mentions the death of Plowden and Bell, and then adds:—”I have exterminated those enemies (those who killed Bell and Plowden), that I may get, by the power of God, your friendship.” He concludes by saying, “See how the Islam oppress the Christian!”

Theodore’s army at this time consisted of some 100,000 or 150,000 fighting men; and if we take as the average four followers for every soldier, his camp must have numbered between 500,000 and 600,000 souls. Admitting, also, the population of Abyssinia to be nearly 3,000,000, about one fourth of the number had to be paid, fed, and clothed by the contributions of the remainder.

During a few years, such was Theodore’s prestige that this terrible oppression was quietly accepted; at last, however, the peasants, half-starved and almost naked, finding that with all their sacrifices and privations they were still far from satisfying the daily increasing demands of their terrible master, abandoned the fertile plains, and under the guidance of some of the remaining hereditary chiefs, retired to the high plateaus, or concealed themselves in secluded valleys. In Gwejam, Welqayt, Shewa, and Tigré, the rebellion broke out almost simultaneously. Theodore had for a while to abandon his ideas of foreign conquest, and did his utmost to crush the mutinous spirit of his people. Whole rebel districts were laid waste; but the peasants, protected by their strongholds, could not be reached: they quietly awaited the departure of the invader and then returned to their desolated homes, cultivating just enough for their maintenance; thus, with only a few exceptions, the peasants evaded the terrible vengeance of the now infuriate Emperor. His immense army soon suffered severely from this mode of warfare. Each year the provinces which the soldiers could plunder became fewer; severe famines broke out; large districts such as Dembeeya, the granary of Gwender and of central Abyssinia, lay waste and uncultivated. The soldiers, formerly pampered, now in their turn half starved and badly clad, lost confidence in their leader; desertions were numerous; and many returned to their native provinces, and joined the ranks of the discontented.

The fall of Theodore was even more rapid than his rise. He was still unconquered in the battlefield, as, after the example of Nigusé’s fate, none dared to oppose him; but against the passive warfare of the peasantry and the Fabian-like policy of their chiefs he could do nothing. Never resting, almost always on the march, his army day-by-day becoming reduced in strength, he went from province to province; but in vain: all disappeared at his approach. There was no enemy; but there was no food! At last, reduced by necessity, in order to keep around him some remnants of his former immense army, he had no alternative left but to plunder the few provinces still faithful to him.

When I first met Theodore, in January, 1866, he must have been about forty-eight years of age. His complexion was darker than that of the majority of his countrymen, the nose slightly curved, the mouth large, the lips so small as hardly to be perceived. Of middle size, well knit, wiry rather than muscular, he excelled as a horseman, in the use of the speak, and on foot would tire his hardiest followers. The expression of his dark eyes, slightly depressed, was strange; if he was in good humor they were soft, with a kind of gazelle-like timidity about them that made one love him; but when angry the fierce and bloodshot eye seemed to shed fire. In moments of violent passion his whole aspect was frightful: his black visage acquired an ashy hue, his thin compressed lips left but a whitish margin around the mouth, his very hair stood erect, and his whole deportment was a terrible illustration of savage and ungovernable fury.

Yet he excelled in the art of duping his fellow-men. Even a few days before his death he had still, when we met him, all the dignity of a sovereign, the amiability and good-breeding of the most accomplished “gentleman.” His smile was so attractive, his words were so sweet and gracious, that one could hardly believe that the affable monarch was but a consummate dissembler.

He never perpetrated a deed of treachery of cruelty without pleading some specious excuse, so as to convey the impression that in all his actions he was guided by a sense of justice. For example, he plundered Dembeeya because the inhabitants were too friendly toward Europeans, and Gwender because one of our messengers had been betrayed by the inhabitants of that city. He destroyed Zegé, a large and populous city, because he pretended that a priest had been rude to him. He cast into chains his adopted father, Mayor Haylo, because he had taken into his service a female servant he had dismissed. Tesema Ingida, the hereditary chief of Gaynt, fell under his displeasure because after a battle against the rebels he had shown himself “too severe,” and our first headjailor was taken to the camp and put in chains because he had “formerly been a friend” of the King of Shewa. I could adduce hundreds of instances to illustrate his habitual hypocrisy. In our case, he arrested us because we had not brought the former captives with us; Mr. Stern he nearly killed, merely for putting his hand to his face, and he imprisoned Consul Cameron for going to the Turks instead of bringing him back an answer to his letter.

Theodore had all the dislike of the roving Bedouin for towns and cities. He loved camp life, the free breeze of the plains, the sight of his army gracefully encamped around the hillock he had selected for himself; and he preferred to the palace the Portuguese had erected at Gwender for a more sedentary king, the delights of roaming about incognito during the beautiful cool nights of Abyssinia. His household was well-regulated; the same spirit of order which had introduced something like discipline into his army, showed itself also in the arrangements of his domestic affairs. Every department was under the control of a chief, who was directly responsible to the Emperor, and answerable for everything connected with the department entrusted to him. These officers, all men of position, were the superintendents of the Tej (honeywine) makers, of the women who prepared the large flat Abyssinian bread, of the wood-carriers, of the water girls &c.; others, like the “Balderas,” had the charge of the Royal stud, the “Azazh” of the domestic servants, the “Bej’Rond” of the treasury, stores, &c.; there were also the Agafaris or introducers, the Leeqe’Mekwas or chamberlain, the Afe’Nigus or mouth of the king.

Strange to say, Theodore preferred as his personal attendants those who had served Europeans. His valet, the only one who stood by him to the last, had been a servant of Barroni, the vice-consul at Mitsiwa (Ottoman Red Sea port; Modern-Day Eritrea). Another, a young man named Paul, was a former servant of Mr. Walker; others had at one time been in the service of Ploweden, Bell, and Cameron. Excepting his valet, who was almost constantly near his person, the others, although they resided in the same inclosure, had more especially to take care of his guns, swords, spears, shields, &c. He had also around him a great number of pages; not that I believe he required their presence, but it was an “honor” he bestowed on chiefs entrusted with distant commands or with the government of remote provinces. Almost all the duties of the household were performed by women; they baked, they carried water and wood, and swept his tent or hut, as the case might be. The majority of them were slaves whom he had seized from slave-dealers at the time he made “manly” efforts to put a stop to the trade. Once a week, or more often as the case required, a colonel and his regiment had the honor of proceeding to the nearest stream, to was the Emperor’s linen and that of the Imperial household. No one, not even the smallest page, could, under the penalty of death, enter his harem. He had a large number of eunuchs, most of them Galas, or soldiers and chiefs who had recovered from the mutilation the Galas inflict on their wounded foe. The queen or the favorite of the day had a tent or house to herself, and several eunuchs to attend upon her; at night these attendants slept at the door of her tent, and were made responsible for the virtue of the lady entrusted to their care. As for the ordinary women, the objects of passing affections or of stronger passions that time had quenched, a tent or hut in common for ten or twenty, one or two eunuchs and a few female slaves for the whole, was all the state he allowed these neglected ladies.

Theodore was more bigoted than religious. Above all things he was superstitious; and that to a degree incredible in a man in other respects so superior to his countrymen. He had always with him several astrologers, whom he consulted on all important occasions—especially before undertaking any expedition,—and whose influence over him was unbounded. He hated the priests, despised them for their ignorance, spurned their doctrines, and laughed at the marvelous stories some of their books contain; but still he never marched without a tent church, a host of priests, debteras (cantors and scribes), and deacons, and never passed near a church without kissing its threshold.

Though he could read and write, he never condescended to correspond personally with any one, but always accompanied by several secretaries, to whom he would dictate his letters; and so wonderful was his memory that he could indite an answer to letters received months, nay years, before, dilate on subjects and events that had occurred at a far remote period. Suppose him on the march. On a distant hillock arose a small red flannel tent—it is there where Theodore fixed his temporary abode and that of his household. To his right is the church tent; next to his own the queen’s, or that of the favorite of the day. Then came the one allotted to his former lady friends, who traveled with him until a favorable opportunity presented itself of sending them to Magdala, where several hundreds were dwelling in seclusion, spinning cotton for their master’s shemas (white tunics and shawls) and for their own clothes. Behind were several tents for his secretaries, his pages, his personal attendants, and one for the few stores he carried with him. When he made any lengthened stay at a place he had huts erected by his soldiers for himself and people, and the whole was surrounded by a double line of fences. Though not wanting in bravery, he never left anything to chance. At night the hillock on which he dwelt was completely surrounded by musketeers, and he never slept without having his pistols under his pillow, and several loaded guns by his side. He had a great fear of poison, taking no food that had not been prepared by the queen or her “remplaçante;” and even then she and several attendants had to taste it first. It was the same with his drink: be it water, Tej, or areqé (anise plant alcoholic drink; i.e. ouzo, araq, absinthe), the cup-bearer and several of those present at the time had first to drink before presenting the cup to his Majesty. He made, however, an exception in our favor one day that he visited Mr. Rassam at Gafat. To show how much he respected and trusted the English, he accepted some brandy, and allowing no one to taste it before him, he unhesitatingly swallowed the whole draught.

He was a very jealous husband. Not only did he take the precautions I have already mentioned, but (except in the last months of his life when it was beyond possibility for him to do otherwise) he never allowed the queen or any other lady in his establishment to travel with the camp. They always marched at night, well concealed, with a strong guard of eunuchs; and woe to him who met them on the road, and did not run his back on them until they had passed! On one occasion a soldier who was on guard crept near the queen’s tent, and, taking advantage of the darkness of the night, whispered to one of the female attendants to pass him a glass of Tej under the tent. She gave him one. Unfortunately, he was seen by a eunuch, who seized him, and at once brought him before his Majesty. After hearing the case, Theodore, who happened to be in good spirits that evening, asked the culprit if he was very fond of Tej; the trembling wretch replied in the affirmative. “Well, give him to wanCHas (large horn cups; trophies) full to make him happy, and afterwards fifty lashes with the jiraf (long hippopotamus whip) to teach him another time not to go near the queen’s tent.” Evidently, Theodore, with a large experience of the beau sexe of his country, was profoundly convinced that his precautions were necessary. On one of his visits to Magdala, one of the chiefs of that amba made a complaint to him against one of the officers of the Imperial household, whom he had caught some time before in his lady’s apartment. Theodore laughed, and said to him, “You are a fool. Do I not look after my wife? And I am a king.”

Theodore was always an early riser; indeed, he indulged in sleep but very little. Sometimes at two o’clock, at the latest before four, he would issue from his tent and give judgment on any case brought before him. Of late his temper was such that litigants kept out of his way; he nevertheless retained his former habits, and might be seen, long before daybreak, sitting solitary on a stone, in deep meditation or in silent prayer. He was also very abstemious in his food, and never indulged in excesses of the table. He rarely partook of more than one meal a day; which was composed of injera (The pancake loaves made of the small seed of the Téf) and red pepper, during fast days; of wéT, a kind of curry made of fish, fowl, or mutton, on ordinary occasions. On feast days he generally gave large dinners to his officers, and sometimes to the whole army. At these festivals the brndo (raw beef) would be equally enjoyed by the sovereign and by the guests. At these public breakfasts and dinners the King usually sat on a raised platform at the head of the table. No one has ever been known, except perhaps Bell, to have dined out of the same basket at the same time as Theodore; but when he desired specially to honor some of his guests, he either sent them some food from his basket, or had others placed on the platform near him, or, what was a still higher honor, sent to the favored one his own basket with the remains of his dinner.

Unfortunately, Theodore had for several years before his death greatly taken to drink. Up to three or four o’clock he was generally sober and attended to the business of the day; but after his siesta he was invariably more or less intoxicated. In his dress he was generally very simple, wearing only the ordinary shema, native-made trousers, and an European white shirt; no shoes, no covering to the head. His rather long hair—for an Abyssinian—was divided in three large plaits, and allowed to fall on his neck in three plaited tails. Of late he had greatly neglected his hair; for months it had not been plaited; and to show the grief he felt on account of the “badness” of his people, he would not allow it to be besmeared with the heavy coating of butter which Abyssinians delight. On one occasion he apologized to us for the simplicity of his dress. He told us that during the few years of peace that followed the conquest of the country, he used often to appear in public as a king should do; but since he had been by the bad disposition of his people obliged to wage constant war against them, he had adopted the soldier’s raiments as more becoming his altered fortune. However, after his fall became imminent, he on several occasions clad himself in gorgeous costumes, in shirts and mantles of rich brocaded silks, or of gold-embroidered velvet. He did so, I believe, to influence his people. They knew that he was poor, and though he hated pomp in his own attire, he desired to impress on his few remaining followers that though fallen he was still “the King.”

During the lifetime of his first wife and for some years afterwards, Theodore not only led an exemplary life, but forbade the officers of his household and the chiefs more immediately around him to live in concubinage. One day in the beginning of 1860 Theodore perceived in a church a handsome young girl silently praying to her matron saint, the Virgin Mary. Struck with her beauty and modesty, he made inquiries about her, and was informed that she was the only daughter of Gate-Commander Wibé, the Prince of Tigré, his former rival, whom he had dethroned, and who was then his prisoner. He asked for her hand, and met with a polite refusal. The young girl desired to retire into a convent, and devote herself to the service of God. Theodore was not a man to be easily thwarted in his desires. He proposed to Wibé that he would set him at liberty, only retaining him in his camp as his “guest,” should the Prince prevail on his daughter to accept his hand. At last Mrs. Tiru’Nesh (thou fem. art pure) sacrificed herself for her father’s welfare, and accepted the hand of a man whom she could not love. This union was unfortunate. Theodore, to his great disappointment, did not find in his second wife the fervent affection, the almost blind devotion, of the dead companion of his youth. Mrs. Tiru’Nesh was proud; she always looked on her husband as a “parvenu,” and took no pains to hide from him her want of respect and affection. In the afternoon, Theodore, as it had been his former habit, tired and weary, would retire for rest in the queen’s tent; but he found no cordial welcome there. His wife’s looks were cold and full of pride; and she even went so far as to receive him without the common courtesy due to her king. One day when he came in she pretended not to perceive him, did not rise, and remained silent when he inquired as to her health and welfare; she held in her hand a book of psalms, and when Theodore asked her why she did not answer him, she calmly replied, without lifting up her eyes from the book, “Because I am conversing with a greater and better man than you—the pious King David.”

Theodore sent her to Magdala, together with her new-born son, Alem’Ayehu (I have seen the world), and took as his favorite a widowed lady from Yeju, named Mrs. Temeño (I lusted), a rather coarse, lascivious-looking person, the mother of five children by her former husband; she soon obtained such an ascendancy over his mind that he publicly proclaimed “that he had divorced and discarded Tiru’Nesh, and that Temeño should in future be considered by all as the queen.” Soon Mrs. Temeño had numerous rivals; but she was a woman of tact; and far from complaining, she rather encouraged Theodore in his debauchery, and always received him with a smile. One day she said to her fickle lord, who felt rather astonished at her forbearance, “Why should I be jealous? I know you love but me; what is it if you stoop now and then to pick up some flowers, to beautify them by your breath?”

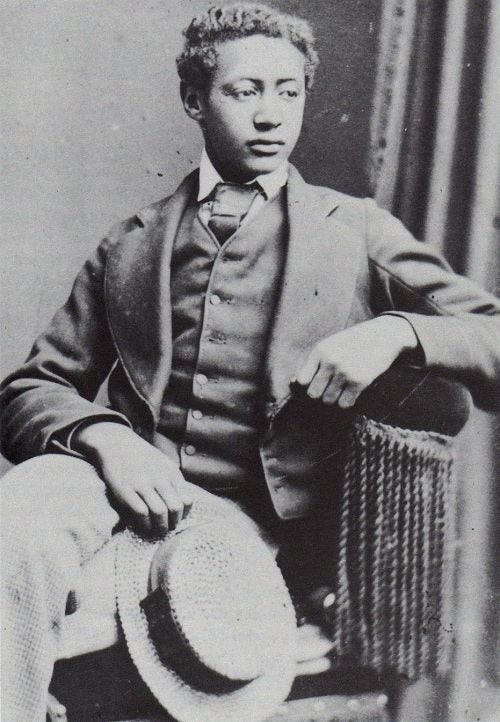

Although Theodore had several children, Alem’Ayehu is the only legitimate one. The eldest, a lad of about twenty-two, called Prince Meshesha, is a big, idle, lazy fellow. Though at Zegé, Theodore introduced him to us, and desired us to make him a friend with the English, he did not love him: the young man was, indeed, so unlike the Emperor that I can well understand Theodore having had serious doubts of his being really his son. The other children, five or six in number, the illegitimate offspring of some of his numerous concubines, resided at Magdala, and were brought up in the harem. He seems to have taken but very little notice of them: but every time he passed through Magdala he would send for Alem’Ayehu, and play with the boy for hours. A few days before his death he introduced him to Mr. Rassam, saying, “Alem’Ayehu, why do you not bow to your father?” And after the audience he sent him to accompany us back to our quarters.

Mrs. Tiru’Nesh, Alem’Ayehu’s mother, never made any complaint; though forsaken by her husband, she remained always faithful to him. She spent usually the long days of her seclusion reading the books she delighted in—the psalms, the lives of the saints and of the Virgin Mary—and bringing up by her side her only son, for whom she had a deep affection. Although she had never loved her husband, in difficult times she bravely stood by his side. When Mineelik, the King of Shewa (and later Emperor of Ethiopia), made his demonstration before the amba, and treachery was feared, she sent out her son and made all the chiefs and soldiers swear fidelity to the throne. Two days before his death, Theodore sent for the wife he had not seen for years, and spent part of the afternoon with her and his son.

After the storming of Magdala, Mrs. Tiru’Nesh, and her rival Mrs. Temeño, were told to come to our former prison, where they would meet with protection and sympathy. It fell to my lot to receive them on their arrival; and I did my utmost to inspire them with confidence, to assuage their fears, and to assure them that under the British flag they would be treated with scrupulous honor and respect.

It was on the 14th of April, 1866, that Theodore, still powerful, had treacherously seized us in his own house; and strange to say, on the 14th of April, two years afterwards, his dead body lay in one of our huts, while his wife and favorite had to seek shelter under the roof of those whom he had so long maltreated.

Both his queens and Alem’Ayehu accompanied the English army on its march back. Mrs. Temeño left, with feelings of gratitude for the kindness and attention she had received at the hands of the English commander-in-chief, as soon as she could with safety return to her native land, Yeju; but poor Tiru’Nesh died at Aikulet. Her child, Alem’Ayehu, the son of Theodore, and grandchild of Wibé, has now reached the English shore, an orphan, an exile, but well cared for.

Notes:

-Reading about my aunt Tiru’Nesh’s dual piety (rooted in Scripture and prayer) and loyalty to the throne imprints a profound sense of pride in me. Her and her son, through her father, are seeds of Susnyos, Emperor of Ethiopia, and the Solomonic Dynasty writ large. Her humbling of the social-climber Emperor Theodore comes from knowledge of her greater proximity to Solomonic lineage, but alas, in Ethiopia, it is not blood alone but blood and merit that get you the throne.

-The conspiracy factoidist in me cannot help but think their was some foul-play in the life and death of Prince Alem’Ayehu. There are ostensible safety reasons for why the Queen Victoria would take him under her protection, like the many Ethiopian rivals that may have come for him out of vengeance or lust of power, but something does not sit right with me about his early demise as he comes of age, and the refusal to let him return to Ethiopia whilst living and the continued refusal to in 2024 send his remains back to Ethiopia. Fishy.

-The Yeju are allegedly assimilated Oromo, originally part of the Yemenite contingent of the Ottoman-Yemenite-Adelite alliance, led by Gen. Ahmed the Left-Handed against Ethiopia and her allies the Portuguese, in the 16th Century A.D.