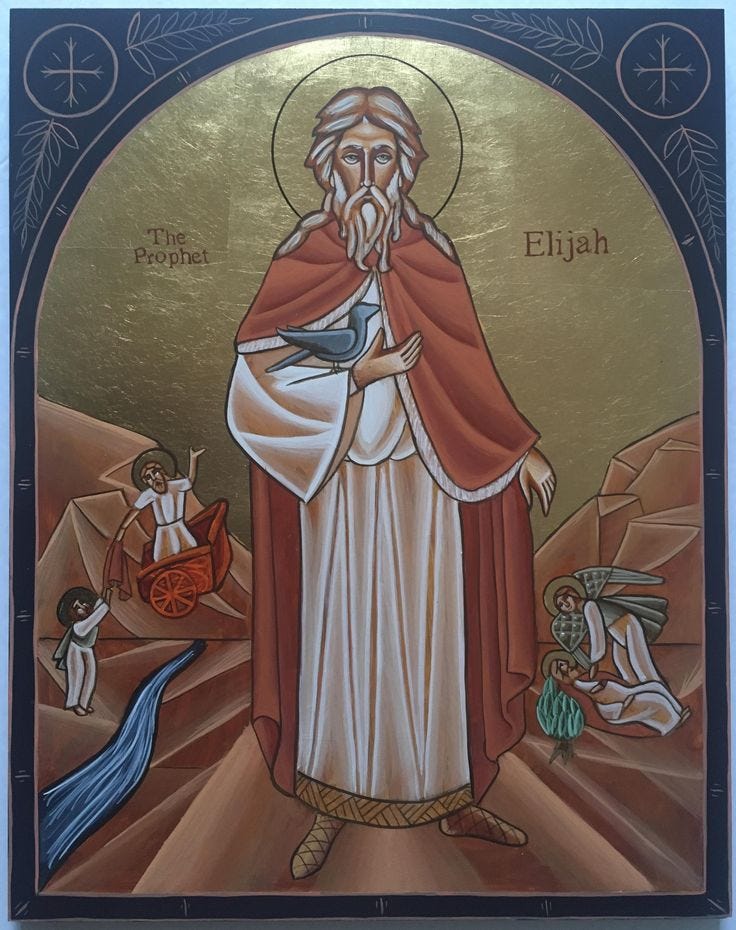

Elements - Volume I: The Transfiguration of Elijah - Earth & Water

Book Review

Editorial Note:

This is the novel I have heard most discussed in my circles since it was released a few years ago. The author is actually anonymous. Many extremely online folks self-identify as anons, but they are in-fact pseudons. And yet, very quickly, if you know you know, it can be noticed that he is a he, and he is a priest of the Oriental Orthodox Christian Church, and more specifically a Coptic priest.

I am about 90% certain that we are a mere two degrees of separation from each other, but I shall not push my contacts further. A Panamanian rastaman named Daniel once chided me in our cathedral in South Central Los Angeles after having praised me for some translation work that I did not attach my name to. He says, “to be anonymous can seem humble because you do not want to take the glory or credit, but it can also be seen as a way to dodge accountability from critics.” So far, in this case, the critics seem to be in favor.

by: Bethel Tamirat Kebede

(bethelkebede22 at gmail dot com; IG at beth__el)

When God wanted to create fish, He spoke to the sea. When God wanted to create trees, He spoke to the earth. But when God wanted to create man, He turned to Himself.

When I read this, I was hooked.

Imagine witnessing a saint who lives on the same timeline as you. I saw how a person can be transformed and completely submit their life to Jesus Christ.

I started Elements back in November 2023—while waiting for the train. I remember that moment so clearly. My heart needed inspiration, and this book delivered bountifully.

The book charts the life and transformation of Elijah. His evolution is not portrayed as a sudden miracle, but as a gradual, intimate transformation. The author allows readers to witness Elijah from infancy through adulthood.

One of the book’s strengths lies in its cultural and ecclesiastical rootedness. I found all the traditions in the church and in Elijah’s life so familiar, as if he were someone I knew from back home in Ethiopia. His faith informs his worldview, his habits, and the rhythm of his life. The reverence toward our Mother the Holy Virgin Mary touched my heart. The feasting-and-fasting cycle of the Orthodox Church — and so much more — give the book depth and bring the storyline to life.

The author skillfully balances contemporary relevance with spiritual gravity. He seems aware of how this crooked generation values sarcasm, uses contemporary slang, and engages with secular culture. There is a humility in the storytelling. The humor and modern references do not distract — they invite. They encourage readers not just to observe but to participate and reflect on their own spiritual notetaking and engagement with truth.

The characters are incredibly relatable; it feels like you could find each one of them in the real world. Each character carries a unique spiritual and emotional imprint that helps the reader connect deeply — not just with their actions, but with their inner journey.

Have you ever asked: How do we cultivate the kind of love for God that consumes heart, soul, and mind? (Mark 12:30)

Through Elijah, the novel suggests that it is possible — not easy, not instant, but profoundly possible.

As I kept reading, I found myself no longer doubting the saints we venerate in our Church — Abune Teklehaymanot, Abune Gebremenfesqidus, Abune Aregawee, to name a few — and the Synaxarion stories we hear every day (may their blessings and prayers be upon us). Their stories once seemed unreal. Elements clarified why I had doubts, and more importantly, it clarified how they lived, why they did what they did, and how they came to love the Lord with such depth.

The book doesn’t try to prove these accounts as historical facts, but it offers a lens through which such lives make sense. It shows that sanctity is not an abstract ideal, but a living possibility — even in the modern age.

Elijah reads books that I can actually find in bookstores — and you might find yourself bookmarking pages and taking notes from the same poems and quotes, just as I did. He reflects deeply on what he reads, and he shares his notes as if inviting us to do the same. You see him living with and among people in the world — literally — yet speaking truth with clarity and conviction.

Overall, I would highly recommend this book to anyone who is yearning to love God more deeply and to anyone wondering what holiness might look like in the 21st century. It speaks to readers who are seeking — whether consciously or not — a deeper, more intimate relationship with God. For those already rooted in their faith, it offers both companionship and a challenge.

For readers of ARB, it invites thoughtful discussion on theology, character formation, cultural identity, and personal faith. And beyond that, it deserves a place among any meaningful and soul-stirring book collection.

Notes:

Elijah is the editor’s father’s namesake and thus his namesake as well. It is the shortened form of the biblical Hebrew Ely is Yahweh, or my god is the god who revealed himself to Moses; namelessly declaring that he is existence itself. Elijah is the common transliteration from Hebrew to English, and Elias is the same name transliterated from Greek to English. Many English translations of Scripture rely on the Masoretic Hebrew for the Old Testament or Hebrew Bible and the Greek for the New Testament. And so, in the same bible, you will see the same figure called Elijah in the Old Testament and Elias in the New Testament. This is made all the more confusing because these New Testament appearances are references to the Old Testament figure and not another guy with the same name (as in the case with Joseph and Mary and Jacob).