Editorial Note:

The 1990s in Ethiopia ushered in a new regime that formally opposed the Marxist-Leninist junta known as the Derg, but functionally replaced class communism with race communism. This race communism was not even scientifically rooted in population genetics, nor historical dominions, rather in the Westphalian nation-state whose dogmas are behind the balkanization of Yugoslavia (from which Ethan Strauss notes to this day has the best white boys in professional basketball i.e. Nikola Jokić, Luka Dončić, Bogdan Bogdanović, Nikola Vučević, Bojan Bogdanović; not to mention two-time FLOTUS Melania Trump) and the attempted slow-burn balkanization of Ethiopia rooted in top-down assigned language groups and drawn from blueprints of Colonial Era Fascist Italy and the powder barrel propaganda of Roman Prochazka.

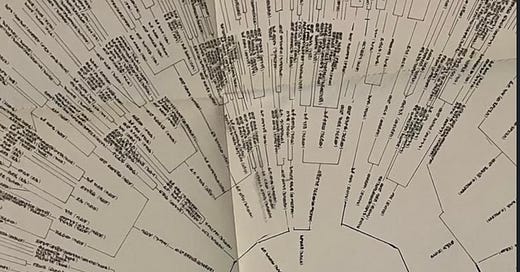

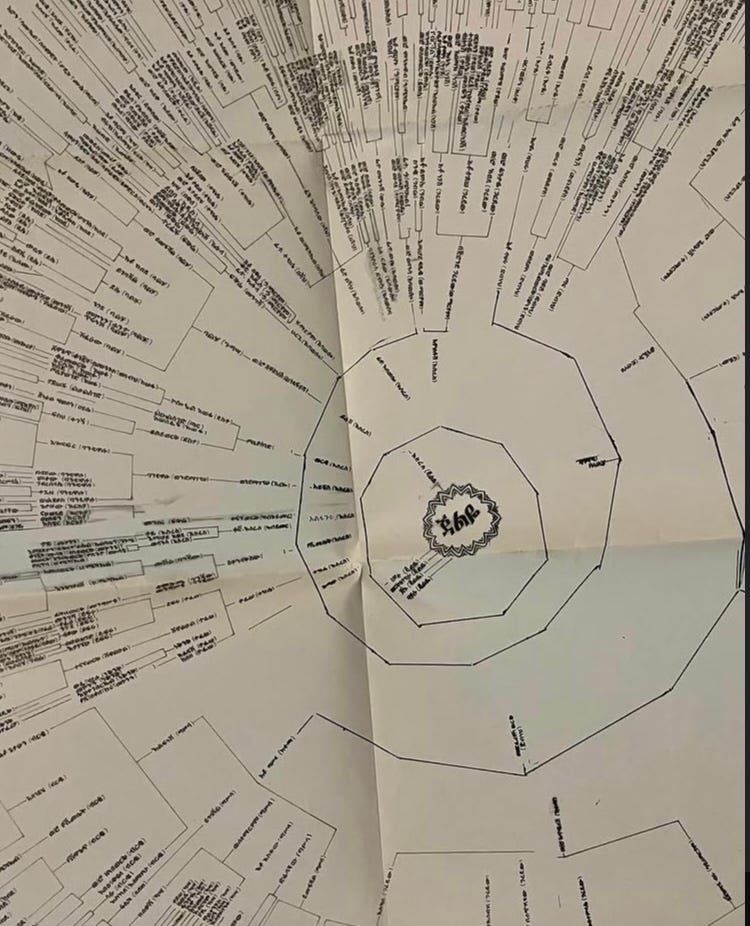

Historic Orthodox Christian monarchist Ethiopia required Solomonic blood for head of state, but also merit aka might, and did not require it at all for head of a dominion or prefecture, and overall did not regard race (certainly as conceived of by TPLF) as all that important. Nevertheless, small-scale tribal and clan knowledge was tremendous. Eyasu reached out to me when he saw that him and I were both of the Adeesgé clan of Northern Shewa, from a post I had made public with my larger lineage written out and put in a beautiful design in a book my paternal grandmother Mrs. Negede Tsehay Agonafer was a contributor to. Many notable people of the 20th and 19th Centuries also belonged to this clan. Here is the story of some.

by: Eyasu Betwos

መልካም:ቤተ:ሰቦች። (melkam béteseboch [sic]; Good Families)

መልካም:ቤተ:ሰቦች። is a deeply personal, multi-generational memoir written by Ras Beetweded (Duke and Beloved of the Emperor) Mekwenin Indalkachew, a key figure in Ethiopia's imperial history. As the grandson of Weyzero (Mrs.) Qonjeet Dibneh, one of the principal matriarchs in the story and the mother of Ras Tesema Nadew and Weyzero Abonesh Mekwenin, Mekwenin writes with both reverence and intimacy. His narrative is a tribute not just to family but to a way of life that interweaves devotion, sorrow, endurance, and service. The story, originally written in Amharic, captures the spiritual and communal legacy of rural Ethiopian nobility during the late 19th century, offering both a vivid portrait of its traditions and a profound reflection on its values.

The story begins in the lush region of Adeesgé, where Mekwenin was born. The author recalls this region as a haven blessed with fertile fields, abundant springs, fruit-bearing trees, and shade giving forests. Birds chirp in varied colors, and livestock roam freely, nourished by the verdant surroundings. The land itself becomes a silent character in the narrative, sustaining not only the body but the spirit of the community. This atmosphere of harmony and sacred ecology reflects the peaceful order upheld by the two sisters, Medfereeyash and Qonjeet, who are at the heart of the memoir. Their daily lives and spiritual rhythms are deeply embedded in the land, which in turn symbolizes their moral clarity and selflessness.

Weyzero Medfereeyash Dibneh and Weyzero Qonjeet Dibneh are not merely remembered as noblewomen. They are presented as the spiritual nucleus of their extended family, embodying the ideals of Christian charity, maternal leadership, and communal responsibility. Their wealth, rather than isolating them, becomes a tool for service. They feed not only their family but also the clergy, the poor, and the orphaned. They raise the children of others alongside their own, insisting that no child in their orbit is treated as lesser. This moral consistency defines the legacy they pass on, and the community they build around them functions more like a convent or spiritual compound than a typical aristocratic estate.

Their decision to combine households, to pool property and resources, and to function as one unified family, defied the norms of even other noble families. They maintain a shared account, manage a common staff, and raise their children in one collective framework. Their unity is a spiritual act as much as it is a practical one. The household's routine revolves around prayer, service, fasting, and communal meals. They awaken together for midnight vigils and morning prayer, hosting priests and blessing their grandchildren. In one especially symbolic gesture, they forbid harm to birds on their land, teaching the children to show mercy to even the smallest of God’s creatures.

The memoir does not simply canonize these women. It shows the human cost of their virtue. Tragedy is a recurring presence in their lives, and the grief they endure is described with restraint but also gravity. The loss of sons in battle, the death of daughters during childbirth, and the killing of sons-in-law in military service stack sorrow upon sorrow. Yet their response is never despair. Instead, they continue praying, fasting, and comforting others. Mekwenin makes it clear that the strength of these women was not in avoiding suffering, but in enduring it with grace.

The author draws attention to the influence these women had on generations of descendants. Their children and grandchildren are shaped not by privilege but by discipline. Many would go on to serve in positions of influence within the imperial system. Their moral training began early. They memorized scriptures, learned to respect elders, and understood the responsibilities that came with status. One of the most beautiful depictions in the memoir is of children playing beneath a massive, centuries-old sycamore tree, acting out imagined futures as farmers, priests, generals, and scholars. These games foreshadow the real responsibilities they would take on, many of them becoming statesmen, advisors, or military leaders.

The memoir captures the physical and emotional landscape of the family compound in meticulous detail. The architecture itself tells a story. The oldest homes are made from small stones and carved wood, with thick doors and modest materials, but they are filled with memory and meaning. One building houses an assembly room. Another serves as a school and dormitory for children. There are places for prayer, for receiving guests, for tending to the sick, and for feeding clergy. Each space serves a purpose rooted in service and spiritual discipline. The compound is not only a home but a microcosm of an ideal community, where order, respect, and divine reverence govern every interaction.

A particularly moving episode in the memoir recounts Mekwenin’s childhood visit to a forest burial site, guided by a servant who wanted to show him the final resting place of his father. This event becomes a moment of awakening for the young narrator. The simple coffin, the scent of damp soil, the scattered bones, and the sense of finality imprint themselves deeply on the child’s consciousness. This is not a horror story. It is a reflection on mortality and legacy. The boy’s questions about death, dignity, and remembrance are answered not through sermons, but through presence, silence, and prayer.

Another memorable scene involves a large gray rooster, nicknamed "the Sunday rooster," who instinctively crows at midnight, waking the sisters for their vigil. The animal’s spiritual utility, the way it naturally syncs with their liturgical rhythm, symbolizes the harmony between faith and nature that defines their household. This is one of many small details that elevate the memoir from personal recollection to cultural document. Everything from timekeeping to cooking to funeral preparation is infused with ritual, sacred intent, and love.

The transition from rural life in Adeesgé to imperial life in Adees Abeba is another central arc in the memoir. When Mekwenin is eventually brought to the capital, he carries with him not only the values taught by his grandmother and great-aunt, but also their prayers and hopes. Even amid the elegance and complexity of court life, he remains grounded in their spiritual formation. The shift is not one of abandonment, but of expansion. The capital city becomes the stage upon which the virtues taught in the countryside are lived out. The tension between spiritual simplicity and imperial responsibility is real, but Mekwenin approaches it with humility and purpose.

The literary style of the memoir reflects this tension. Mekwenin writes with lyrical precision but avoids pretension. His voice is clear, respectful, and emotionally nuanced. He uses oral storytelling traditions as a foundation but elevates them through careful structure and poetic insight. The pacing is deliberate. Descriptions are not rushed. Every scene, every image, is given space to breathe. This makes the sorrow deeper, the beauty sharper, and the lessons more enduring.

The memoir’s theological undertone is also worth noting. It is not a religious tract, but a lived theology. Suffering is not explained away. It is acknowledged and endured. Faith is not abstract. It is lived through fasting, prayer, mourning, singing, hosting, and sharing. One of the most poignant lines comes when, after a series of deaths, the sisters simply say, "the Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord" (Job 1:21). It is this posture of surrendered trust that defines the spiritual foundation of the family.

Ultimately, መልካም:ቤተ:ሰቦች። is not just a memoir. It is a vision. A vision of what home, womanhood, faith, and legacy can be. It is a rare literary work that preserves a moral universe, showing how families can be the engine of both spiritual formation and national service. Ras Beetweded Mekwenin Indalkachew offers a work that is as rich in detail as it is in spirit. Through it, he preserves not just memory, but meaning. He reminds us that true nobility is not inherited but lived. And that the greatest legacy we leave is not in what we own, but in how we serve.

Post Scriptum:

-Note that when writing about Ethiopians, as Prof. Raymond Silverman well knows, you use their first name rather than their 'last’ name, because the ‘last’ name is no family name but just the first name of their father.

-My grandmother Negede in her last two years of life (2018-2019) repeated the same biblical quote (Job 1:21) to me over and over again in Ge’ez and Amharic

Cool insights... but Medfereeyash always makes me lol, even knowing the meaning (sort of).