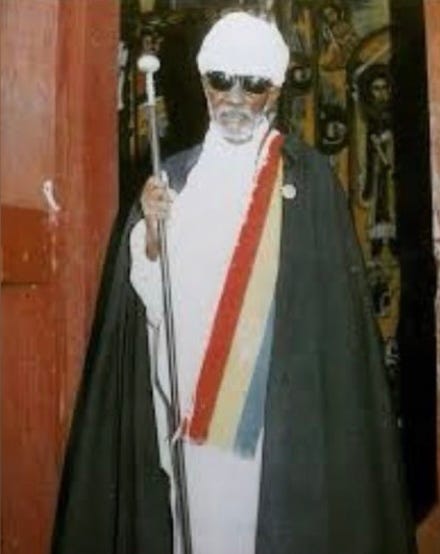

The following is a guest commentary from Dcn. mihret melaku, friend of the Philosophy of Art & Science podcast, and student of aqwaqwam (noneucharistic instrumental liturgy), qidasé (eucharistic a cappella liturgy), and qiné (poetry) in the Ethiopian Orthodox tewahdo Church, and theology and preaching in the Orthodox Church writ large. I asked him to clarify one of the subcategories of aqwaqwam for me, that just so happens to mesh well (for those who know our tradition of wax-and-gold) with my name (hénok) and my son’s name (hzqél); the latter of which can be played with and modified to zeeq, for short.

I have lightly edited his words in order: to match the style guide of Aksum Herald as much as is humanly possible, whilst retaining his authorial voice, and gently introduce you to the technical terms of ge’ez rite hymnography. Read carefully. And enjoy!

It is a derived form of the term ዝቅ (ziq; lower yourself, get down, get under, beneath). It was developed by ሊቃውንተ ጐንደር (masters of gwender) during the time of አፄ ኢያሱ (Emperor Joshua the Great) who loved to attend mahilét (noneucharistic instrumental liturgy). During a ክብረ በዓል (annual feast) while the king of kings would go around the church in a formal procession before entering the church, the ሊቃውንት (masters) wanted to lengthen the mahilét so that then he would have time to listen to some of the mahilét when he entered, thus they devised the idea of adding something under each melk (image and likeness saluting and rhyming chanted poetry) which they chanted with ጸናጽል (sistra). This affixed secondary hymn “beneath” each melk became known as a ዚቅ (zeeq). Each ziq has a miscellaneous origin, it can come from digwa (St. Jared the Aksumite’s hymnal for every day of the year), from zimaré (St. Jared the Aksumite’s communion hymnal), from qidasé, from metshaf (the Aksumite school for biblical exegesis and patristics), etc. For the longest time, each church in gwender had their own ziqs for feasts. Later on, አለቃ ክፍሌ (aleqa kflé) came out with a book called አባ ጃሌ (aba jalé) which had ziqs and their digwa zéma (melody) and was the first attempt at centralizing ziqs. Then የኔታ ሄኖክ (mylord hénok) wrote the revolutionary መዳልወ አልባብ (medalwe albab), creating አቋቋም ምልክት (aqwaqwam musical notations) for all the ziqs, and thus constructing a written wenber (See, seat of authority) for አቋቋም (aqwaqwam), in addition to kibre beal (annual feasts) and werhawee beals (monthly feasts); with their respective ziqs, milTans, isme lealems, etc (subcategories of aqwaqwam/mahilét). Mylord hénok also wrote aqwaqwam milikit (musical notations) for the mezmur (hymn) of each Sunday, the arbayts, and for qinés.

Later on, he wrote the zikre qal, which was a book with the digwa zéma for additional werhawee beals. The መዳልወ አልባብ (medalwe albab) only had the ግዝት ወርኃዊ በዓላት (mandatory monthly feasts) of St. Michael, the Holy Virgin Mary, and God the Son, the zikre qal additionally contained the monthly feasts of St. John the Evangelist, St. gebre menfes qidus, the Holy Trinity, The Exaltation of the Cross, abune aregawee, St. Cyriacus, keedane’mihret, St. Gabriel, St. Uriel, St. George, St. tekle’haymanot, the Savior of the World, and St. Mercurius.

The idea was that someone who was certified in the መዳልወ አልባብ (medalwe albab) would know how to convert the digwa milikit of the zikre qal into aqwaqwam milikit.

Nowadays, with the art of aqwaqwam milikit down to a science, thanks to mylord hénok, there are even newer books that have created ziqs for even more kibre beals and werhawee beals, and added milikit for melks for those still learning. One such example is ልሳነ መላእክት ወሊቃውንት (lisane melaikt weleeqawnt), which is helpful enough to have ላይ ቤት ምልክት (upper-house musical notations) for ziqs in the places where they diverge from the ታች ቤት ወንበር (lower-house See) of mylord hénok.

For more on ziqs you should get yitbehal zegwender, it explains that there are three different ways you can observe a ziq, depending on how much time you have, but generally every melk has a ziq, usually the ziq comes after the melk with tsenatsil (sistra), but in the lengthiest style of mahilét, a given ziq can be done numerous times, repeatedly oscillating between the melk and said ziq, one time after the melk, and then going back to the melk and sticking the ziq in the middle of the melk.

The former is compared to a father and a son, as a son comes after the father, and the latter is compared to Adam and Eve, with Eve the ziq coming from the middle of Adam the melk.

P.S.

If you are a writer, or an aspiring writer, and ever want a relevant piece of yours published here, my DMs and email inbox remain open. Holla atcha boi.

It’s fascinating and inspiring to read about what we usually attend and observe but never know how it came about!!! .....we need more inquiries into the subject of “ Mahlet “🙏🏽

As always Thanks for sharing and God bless your work! Wanted to also to thank Dn Mihret as well 🙏🏽