Editorial Note:

Most recent POAAS guest, my friend, member of The Ephesus School Network, and our brother Blaise Webster is an independent scholar who writes about the Bible, religion, cinema, literature, history, and music. He is living proof that the Living God creates clean hearts of flesh that He writes His instructions upon, even in the wilderness of North America. Him and I share the unique pleasure of having had Biblical Hebrew bored into us by Fr. Paul Nadim Tarazi, and thus we write and podcast, to continue to seed the seed.

Some Ethiopian preachers and teachers use Ge’ez phrases like iruq biisee and mefqeré seb (lover of mankind), expecting the faithful Amharic speakers to immediately understand what they mean. I once chided a priest who does this regularly, to no avail. I once found a younger deacon I know, native Amharic speaker, repeating iruq biisee under his breath in the Bethlehem. I started to laugh, then asked him if he knew what he was saying. He said no, but a preacher had said it, and it stuck with him. Blaise knows.

Written by: Blaise Webster

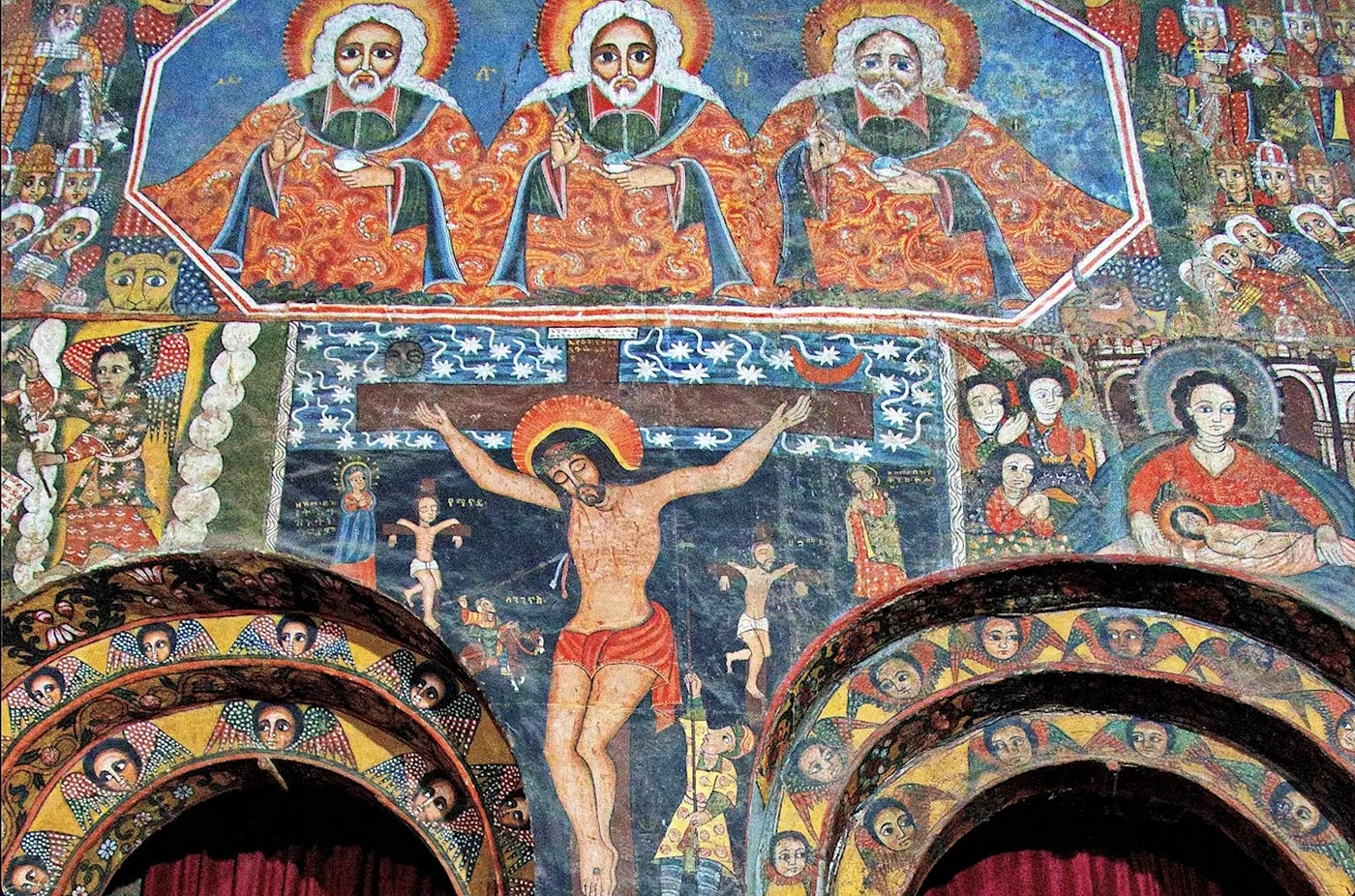

Icon of the Crucifixion; Engaging Wisdom of the EOTC

As the Orthodox Christian world enters into Holy Week, I wanted to quickly reflect on a beautiful tradition within the historic Ge’ez rite of the faith. In a presentation he gave on Ge’ez and Amharic commentary on Galatians 1, Dcn. Henok Elias mentioned a tradition of calling Jesus Christ “the naked man” or ዕሩቅ ብእሲ ‘iruq biisee. The first word, ዕሩቅ, translated as “naked” finds its Arabic counterpart with عرق ‘araqa which means to remove skin from the bone. The Hebrew equivalent of this root is ערק ‘areq which similarly means “to gnaw” and can also refer to “sinews”. Right out of the gate, we are met with incredibly visceral imagery expressed in the tradition of the naked man.

This tradition comes from what is called the andamta corpus which is a collection of Amharic commentary on Ge’ez translations of the Bible. For more information on this commentary tradition, check out this book on the topic.

Galatians 1 from the Andmta (Aksumite School of Biblical Exegesis)

In this commentary on Galatians 1, the commentator writes,

The writ which came from Paulos and not from men. I was taught the teaching by the naked man. I was appointed the appointment by the naked man, not from me. The writ sent from Paulos.

That struck me the first time I heard it because it captures the functionality of Christ’s passion as mainly a spectacle of shame. Western Christianity has often focused much of its attention on the physical pain of the crucifixion, as was brutally demonstrated in Mel Gibson’s graphic portrayal in the The Passion of the Christ. This is undoubtedly a consequence of various models of what is called “satisfaction atonement” and “substitutionary atonement”. The basic idea is that salvation was achieved on the cross by Christ absorbing God’s wrath so that humanity could be spared from it. While the crucifixion was obviously a painful ordeal, the scriptural focus of Christ crucified is rather the shameful nature of his death and the stigma attached to following a “failed” messiah whose naked body was put on display for all to see. Such a spectacular execution, as stated by Deuteronomy 21:23, was a sign that one has been cursed by God. So the point of Christ’s crucifixion is not that he suffered a painful death, it’s that he suffered the death of a cursed individual. In quoting from the aforementioned verse from Deuteronomy, Paul says,

Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us — for it is written, “Cursed is everyone who is hanged on a tree” — so that in Christ Jesus the blessing of Abraham might come to the Gentiles, so that we might receive the promised Spirit through faith. — Gal. 3:13–14

Christ being stripped of his garments brings this shameful death to further dimensions. In the Ancient Near East, to be stripped naked before your enemies was the worst possible way someone could die. The nature of the nakedness and shame also calls to mind the inaugural sin in the book of Genesis where Adam and Eve are at first naked and unashamed, but when they sin, they become ashamed of their nakedness and try to hide from it. Christ, the New Adam, submits to this shame in obedience to his Father and makes himself “naked” unto death. This is literally how the famous “suffering servant” poem in Isaiah 53 goes in Hebrew.

Therefore I will divide him a portion with the many, and he shall divide the spoil with the strong, because he poured out his soul to death (Heb. he made himself naked to death) and was numbered with the transgressors; yet he bore the sin of many, and makes intercession for the transgressors. — Is. 53:12

While this translation appears quite different from what is literal from the original Hebrew, I will take a moment to break down what is happening here and why the translations are so far from the original. The Hebrew of Isaiah 53:12 reads,

אֲשֶׁ֨ר הֶעֱרָ֤ה לַמָּ֙וֶת֙ נַפְשֹׁ֔ו asher ha‘arah lamawet nafshow — that he made naked to death, his life

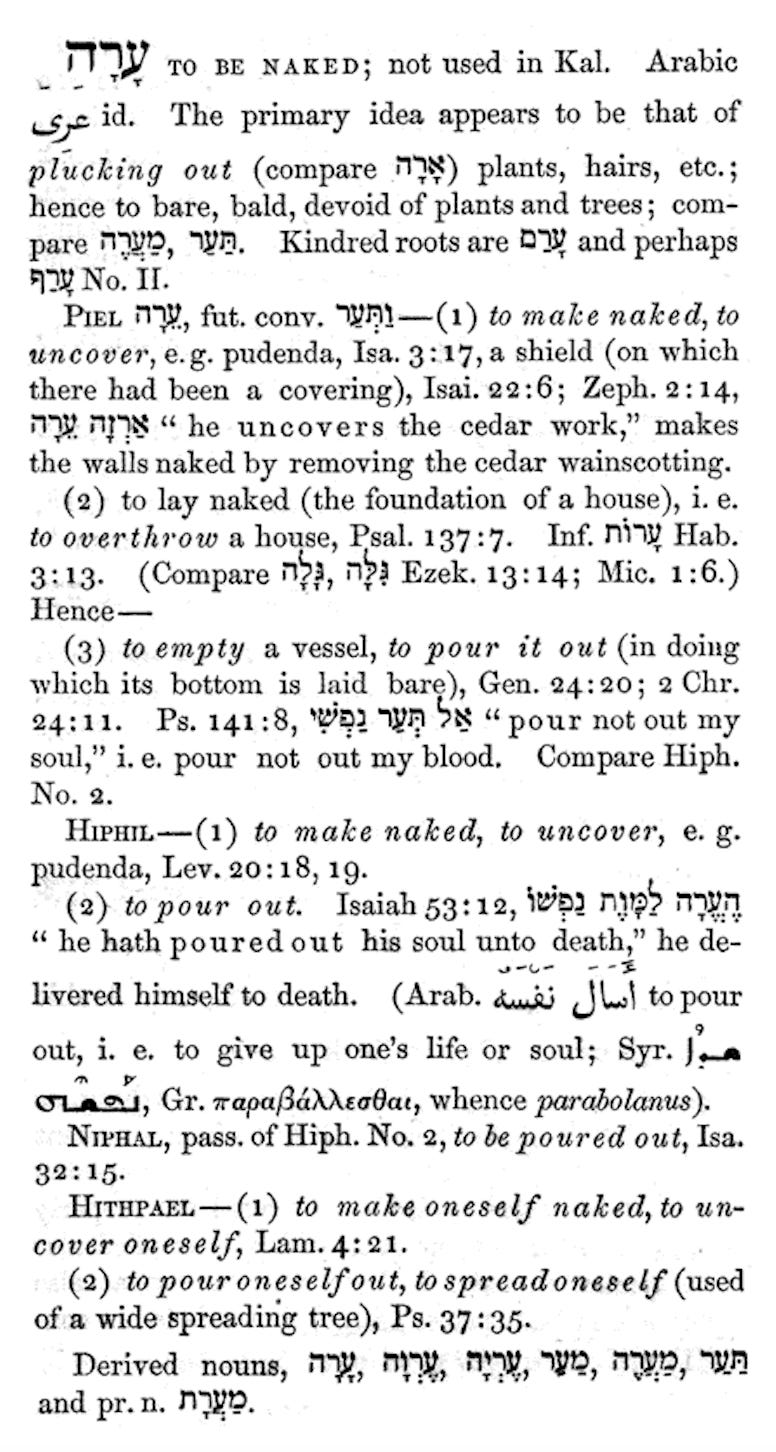

The word in question, of course, is ערה ‘arah — to be naked/ bare. A derivative of this root is עריה ‘eryah — nakedness. This is the exact word used in the great parable of Ezekiel 16 where Jerusalem is likened to a bride in a destitute situation who is taken in by a bridegroom who graciously shows mercy on her, but she becomes a harlot and ends up similarly destitute as she was at the beginning. The word עריה is the key term at both ends of this parable.

I made you flourish like a plant of the field. And you grew up and became tall and arrived at full adornment. Your breasts were formed, and your hair had grown; yet you were naked (עירם) and bare (עריה). — Ezek. 16:7

And I will give you into their hands, and they shall throw down your vaulted chamber and break down your lofty places. They shall strip you of your clothes and take your beautiful jewels and leave you naked (עירם) and bare (עריה). — Ezek. 16:39

Indeed, Jerusalem’s punishment is to be rendered back into that state of “nakedness” and “bareness” that God originally rescued them from. You may have noticed that I highlighted another word used in these Ezekiel passages, which is from ערם ‘arom — naked. The roots are very similar, with only the ending (mem, ם) being different. This is the exact root used in Genesis 3 to describe Adam and Eve’s nakedness. The import of this is that God clothes Adam and Eve (Gen. 3:21) and covers their nakedness and shame. It is analogous to the parable in Ezekiel against Jerusalem, and the punishment at the end of the parable is likewise for God to relinquish that grace and force his people to face their own nakedness and shame. This is ultimately the punishment that Isaiah’s suffering servant takes upon himself, in doing the opposite of what Adam did: obey God fully until the bitter end.

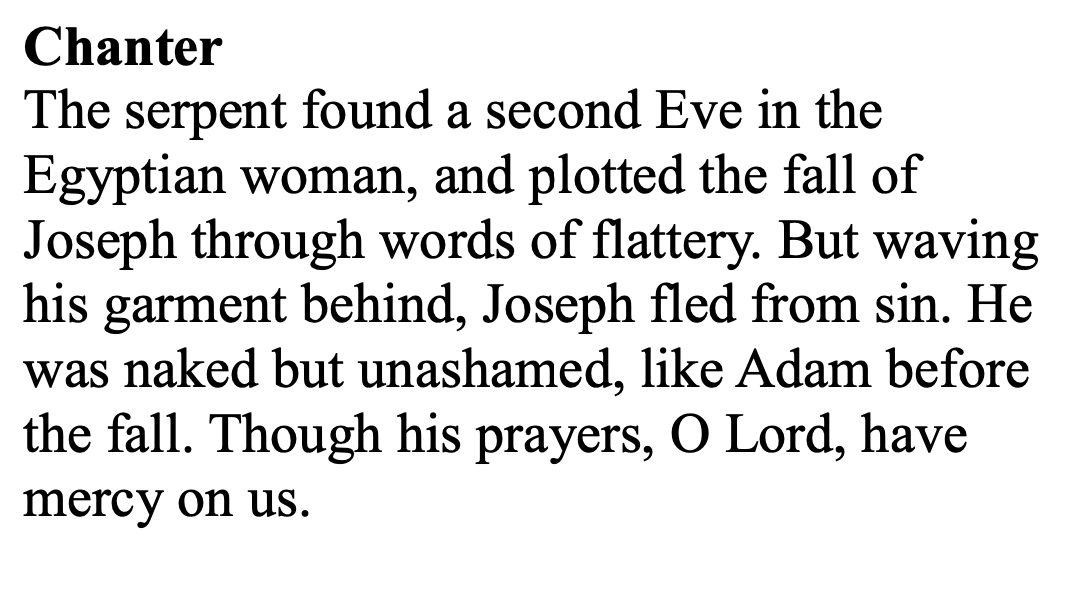

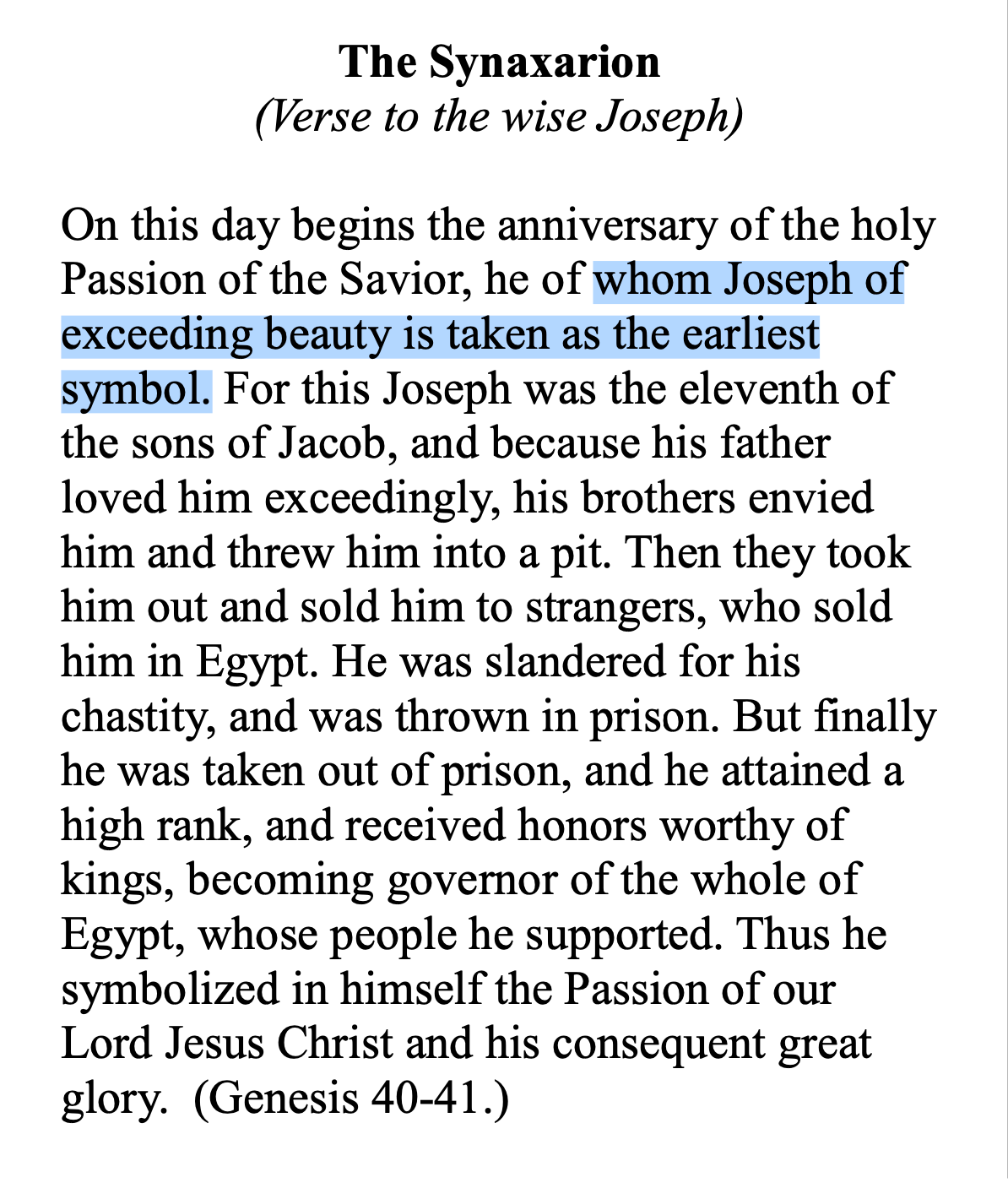

In an interesting verse from the Monday Bridegroom orthros during Orthodox Holy Week, Joseph is likened to Adam (and ultimately Christ) because he left his garment with Potiphar’s wife and fled naked and unashamed (Gen. 39:12).

Here, the author of the hymn is drawing a typology among Adam, Joseph, and Christ as evidenced by the introduction to the service.

So why then is the translation of “pouring” oneself out, or some variation of that, a popular choice? I think the answer mostly has to do with the Septuagint translation on the one hand, and Paul’s allusion to Isaiah 53:12 in his letter to the Philippians on the other. The Septuagint actually omits any word for “pouring oneself out” or “nakedness” and simply says that the servant’s soul was “delivered” to death.

ἀνθ᾽ ὧν παρεδόθη (paredothē, he delivered/ handed over) εἰς θάνατον ἡ ψυχὴ αὐτοῦ — Is. 53:12b, LXX

This is expressed also in the Vulgate version,

eo quod tradidit (he handed over/ “traded”) in morte animam suam — Is. 53:12b, VUL

While this translation is significantly less visceral than the original Hebrew, Paul opts to use the word ἐκένωσεν ekenōsen — emptied in his allusion to Isaiah 53 in Philippians 2:7.

Who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied (ἐκένωσεν) himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. — Phil. 2:6–7

That word ἐκένωσεν, is the Aorist form of κενόω kenoō which refers to completely emptying something of all of its contents. It can also refer to making something void, in a more metaphorical sense. This is actually an intelligent rendering of the Hebrew ערה because it too can also refer to “emptying” or “pouring out”, in the same sense as when something is stripped bare when it is “naked”. Wilhelm Genesius’ famous lexicon tracks all of the different uses that this root has.

Many of these translations seem to be following the terminology of the Septuagint and the Vulgate because to “make oneself naked to death” is a bit awkward in translation. It does not, necessarily, evoke the same imagery in translation. That is why Paul’s unique rendering of that root into κενόω is so brilliant. The suffering servant does not desire to “grasp” his way to equality with God, like Jacob (the heel grabber). Instead, he infinitely reduces himself to nothing and bears the shame of the cross.

And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross. — Phil. 2:8

This, more than anything else, is emphasized by Paul because it is the shame and stigma of Christ crucified which is the very content of his Gospel.

For I decided to know nothing among you except Jesus Christ and him crucified. — 1 Cor. 2:2

New Testament scholar Tom Dykstra comments on Paul’s unique emphasis on the crucifixion, writing,

Paul’s gospel that focuses so single-mindedly on something as awful as the cross and crucifixion can only be “good news” because the message of the cross is essentially one of irony: when others see the crucifixion as a defeat, Paul knows it to be a victory; when others see suffering as cause for sadness, Paul sees it as something to rejoice in and give thanks for. Irony of this sort pervades Paul’s epistles because at the core of his gospel is the message that insiders see a reality that is the opposite of the way outsiders see it. “For the word of the cross is folly to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.” One can hardly read any given chapter of Paul’s epistles without running across some expression of this irony. — Mark, Canonizer of Paul: A New Look at Intertextuality in Mark’s Gospel, p. 96.

For Paul, he must emphasize the shame of the gospel due to the apparent accusation against him from his opponents that he was preaching against the necessity for circumcision in order to make the conversion process easier for gentiles. Their accusation, as reflected in Paul’s letter to the Galatians, was that he was attempting to be “pleasing” to men.

For am I now seeking the approval of man, or of God? Or am I trying to please man? If I were still trying to please man, I would not be a servant of Christ. Gal. 1:10

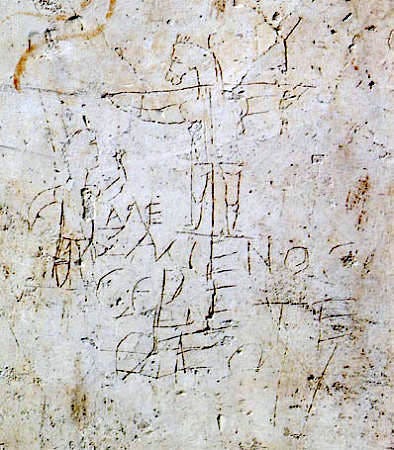

On the contrary, circumcision is something that can be hidden. It is purely a “show of the flesh” as Paul calls it. To become a Christian, especially in the context of Paul’s Roman environment which glorified kingly dynasties and human might, was to become essentially a fool (1 Cor. 4:10). It was to proclaim as lord a man who was put to death by the authorities in the most shameful way. To the Jews, it was a stumbling block because it signified that one was cursed by God. To the Greeks, it was foolishness because Christ was a failure according to their wisdom. This is a shame that cannot be hidden and it is a shame that is not done by marking the body. It is a shame that comes from the proclamation that a naked, crucified man is to you what the great and powerful Caesar is to everyone else. Evidence for this type of shame and the ridicule that came out of it is seen especially in the Alexamenos graffito drawn presumably by a Roman, depicting a man worshipping crucified donkey with text saying “Αλεξαμενος σεβετε θεον” which translates to, Alexamenos worships (his) God.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexamenos_graffito

Thus, like Paul, we must bear the stigmata of Christ (Gen. 6:17), take up our cross, and bear the shame with him. It is interesting that Western models based on the aforementioned “satisfaction” and “substitutionary” atonement theories have Christ’s work as keeping us away from the pain of the cross. In contrast, the Gospel implies that we must instead share in the shame that Christ suffered on our behalf.

For God called you to do good, even if it means suffering, just as Christ suffered for you. He is your example, and you must follow in his steps. — 1 Pet. 2:21

And at every eucharist, we must proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes.

For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes. — 1 Cor. 11:26

So in conclusion, what makes this Aksumite tradition of the “naked man” so special is that it correctly understands the point of Christ’s crucifixion. It is not Jesus’ physical pain alone that is the focus of Paul nor the New Testament, but the fact that Jesus died a cursed death in the most shameful and humiliating way possible. It is Christ’s kenosis, his becoming naked to death and emptying himself of any value, that cancelled the debt of sin (Col. 2:14) and voided the curse of the Law (Gal. 13:13). Becoming this curse is the source of Christ’s suffering in the New Testament and the bearing this stigma is the suffering that Paul carries on in his letters. Yes, physical pain is obviously involved, but pain can also be inflicted in a way that is not traditionally shameful (like falling in warfare, for example). Only when you prioritize the shame, can we interpret correctly Isaiah’s statement that the suffering servant would heal his people via his “wounds” and “stripes” and how Peter can say,

He himself bore our sins in his body on the tree, that we might die to sin and live to righteousness. By his wounds you have been healed. — 1 Pet. 2:24

There Peter paints the perfect picture of what happened to Christ on the cross. His body on the tree is a reference to Christ’s “cursed” death in Galatians 3:13 and his language of dying to sin and living to righteousness is thoroughly Pauline and references the language of baptism.

We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life. — Rom. 6:4

Which is also referenced later in 1 Peter,

Baptism, which corresponds to this, now saves you, not as a removal of dirt from the body but as an appeal to God for a good conscience, through the resurrection of Jesus Christ.— 1 Pet. 3:21

Thus, in Christ’s shameful death as the “naked man”, the wounds he suffered save those who are in Christ, ie those who have died to sin and and live in righteousness. This is the content of Paul’s gospel, and the fulfillment of Isaiah’s suffering servant; the nameless and faceless lamb who takes away the sins of the world.