Editorial Note:

C.C.R. and Giovanni (John) Ellero conducted their scholarship under the Italian colonial and fascist eras. Read their work, and take this under consideration. I believe in reading the works of even my enemies so that reading between the lines some truths may be gleaned. As many of you likely already know, but some may be learning for the first time, the Welqayt Question is one very close to my heart. My maternal grandfather is from there and lived there. His father was the one that was properly ethnically Welqayt (whatever that means), while his mother who raised him was of South Gwender. His father’s side ruled the area for centuries, with a direct descent from their last ancestor on the Solomonic throne Emperor Susnyos. My grandfather gave up his feudal claims to Ajiré (just outside of Dabat), but during the communist era somehow meritocratically became governor of all of Begemder (Gwender), including Welqayt. Having armed his people, and survived an assassination attempt by a communist official, he retired and became an author. In addition to his Amharic memoir and two translations of kings’ chronicles from English to Amharic, he wrote an Opposition Letter to then President Meles in November 1991 (when I was one year old) regarding the blueprint TPLF had released which showed Tigray subsuming Welqayt (and Raya, formerly of Welo not the elite dating service app).

John Ellero, known to the readers of the Rassegna for his interesting monographs on Shewa and Inderta and for his tragic end, which occurred during the Japanese torpedoing of the ship Nova Scotia that was transporting him as a prisoner of war to South Africa, left behind several valuable writings, the result of his investigations in northern Ethiopia. Among these stands out a monograph on Welqayt, a region of which he was in charge. Too extensive to find prompt publication under the current circumstances, it seemed useful to extract from it, in the meantime—where Ellero had exclusively collected oral traditions and personal observations of facts—what might most interest the readers of the Rassegna, elaborating and coordinating it with data and documents that no one could have had in Adee Remets. My not inconsiderable work serves as an act of ultimate homage to a highly capable official, to an unfortunate friend:

-C.C.R. (Carlo Conti Rossini)

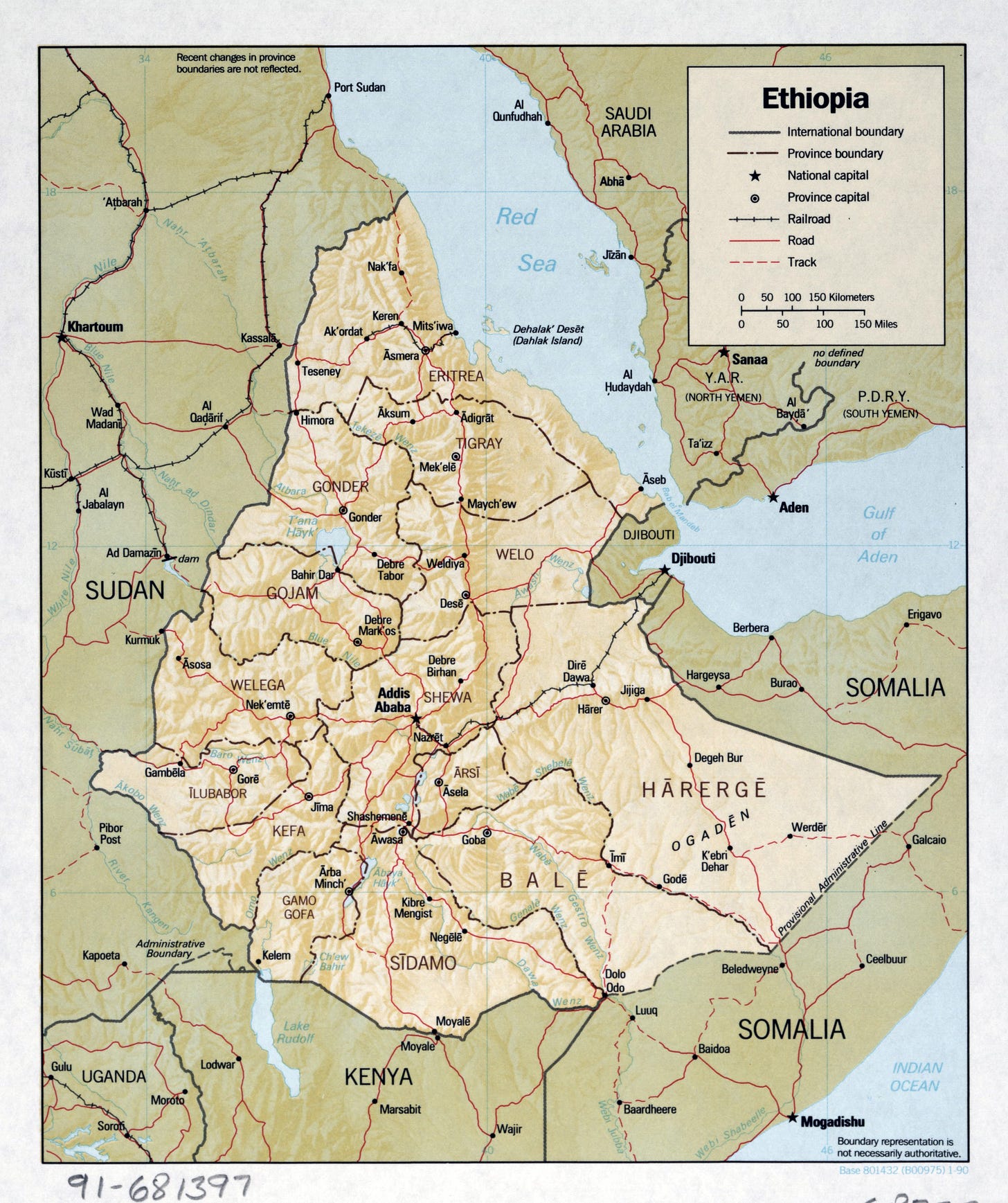

In Abyssinia, it is customary to call Welqayt-Tsegede the extreme projection of the Amhara orographic system, extending northward, isolated by lowlands on three of its sides: Welqayt refers to the northern part, Tsegede the southern part, divided by the Casa River, with its perennial waters, which collects the flow of the Ruba Asa directed southward and itself empties into the Angareb. Avoided by caravans, untouched by European travelers, Welqayt is almost unknown even to Abyssinians, who merely describe it as a wild and mysterious region. It is a rugged mountain stronghold, its isolation increased by periodic floods that make its rivers impassable, deeply entrenched in narrow valleys, either traversing it or forming its boundaries: the Casa, the Angareb, which receives the waters flowing north and east (the Roian or, more accurately, Arrawian, the Doguacum, the Menamene), the Cahma, another significant tributary of the Angareb, and the Seteet-Tekezé. To these notable obstacles is added malaria, which, during and after the season of heavy rains, infests the lower regions. More than a crossroads, Welqayt was a barrier against which the conflicting interests of Sudanese from the west, Beja from the north, Tigrinya from the east, and Amhara from the south came into conflict. In recent centuries, the latter prevailed politically, but they limited themselves to sending tax collectors and disgraced weyzero (noblewomen) there.

The popular etymology of the name Welqayt demonstrates the evaluation that other Abyssinians have of that region and its inhabitants: during the time of Emperors Abrha and Atsbha, the Metropolitan Selama, kesaté birhan (revealer of light), traveled through Tigray blessing its various regions. Only upon his return to Aksum did he realize he had forgotten one region beyond the Tekezé (River), whereupon he exclaimed: "That region welqa qeret! It slipped away!" Welqayt is the land devoid of blessing.

Geographically, it consists of three parts, profoundly different in morphological appearance, climate, and products. The true Welqayt is the highland, a plateau, a narrow strip of cultivable land along the mountain ridge, extending south to north: it lies at an altitude ranging from 1,500 to 2,200 meters (4,921 to 7,218 feet) and does not differ substantially from the other high Abyssinian regions. Below it, except towards the south, is a highly rugged mountain belt, descending from 1,500 to 800 meters (4,921 to 2,625 feet); it comprises a series of steep-walled valleys, difficult to access and traverse, with lush arboreal vegetation and an unhealthy climate. Below this lies a third zone, between 800 and 500 meters (2,625 to 1640 feet), flat, with chalky, highly fertile terrain, deeply carved and varied by the course of streams, exhibiting all the characteristics of a tropical zone. This is the Mezega. Strictly speaking, mezega is "the black, clayey, deeply cracked soil that, due to the compactness of its lower layers, retains the water it absorbs during the rainy season"; it is the walaqd of other Tigriña regions. By extension, Mezega, in Welqayt, Tselemt, Adee Abo, and Shire, is the proper name of the lowland between the slopes of the mountain system and the course of the Tekezé. This study concerns the historical Welqayt, excluding, therefore, the Kefta and Birtukan.

Although isolated from Tigray, Welqayt is usually considered part of it, both because the majority of its population is Tigriña, with some Amhara influence, and because Tigriña is the language, albeit altered in its lexicon to the point of taking on distinct dialectical characteristics. Amharic is understood by a good portion of the population and, so to speak, tolerated in everyday life. A census conducted by the Italian authority confirmed the presence of 2,060 families, of which 1,965 were Christian (318 of whom were former slaves, mostly permanently residing in the Mezega), 73 Muslim, and 22 Felasha (Béte Israel; Ethiopian Jews). Assuming an average of five people per family, the total population is 10,300 inhabitants.

In terms of political-administrative status, Welqayt constituted—and constitutes—[the text is cut off here].

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Aksum Review of Books to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.